Quotient Sets and Topologies

The idea of quotient spaces is interesting to look at because it opens up a class of deformations that, when applied, create fascinating spaces. These are also easy to visualize in some cases and provide a foundation on which more sophisticated concepts are built.

Definitions in the general case

I will quickly define some terms so that we can move to the fun part. For spaces \(X\) and \(Y\), consider a surjective map \(p: X \to Y\) such that a subset \(U \subset Y\) is open in \(Y\) if and only if \(p^{-1}(U)\) is open in \(X\). Such a map is called a quotient map.

The notion of an open set depends on the topology defined on the space, so we try to do this backwards. We will define a topology such that the above condition is satisfied. Given a space \(X\), a set \(A\) and a surjective map \(p: X \to A\), it turns out that we can define a unique topology on \(A\) such that \(p\) becomes a quotient map. Here is how we construct this topology (say \(\tau\)). Define \(U \subset Y\) to be open (i.e. \(U \in \tau\)) if \(p^{-1}(U)\) is open in \(X\). By definition this topology respects the conditions of the quotient map. We can verify that \(\tau\) indeed respects all rules that topologies must follow:

- \(\phi = p^{-1}(\phi)\) and \(X = p^{-1}(A)\). Both of these are open in \(X\), therefore \(\phi, A \in \tau\)

- For a collection \(J\) of open sets in \(A\), the union of these open sets is open, because \(p^{-1}\left( \bigcup_{U \in J} U \right) = \bigcup_{U \in J} p^{-1}(U)\) and the right-hand side is open in \(X\)

- Intersection of a finite number of open sets \(U_1, \ldots, U_n\) is open because \(p^{-1}\left( \bigcap_{i = 1}^{n} U_i \right) = \bigcap_{i = 1}^{n} p^{-1}(U_i)\) and the right-hand side is open in \(X\)

Definitions on partitions

A special case of what we have discussed before arises when we define the quotient topology on a partition of \(X\). In the setup of the previous section, we now consider \(A\) to be a partition of \(X\). The map \(p\) is now just the canonical projection map, that is, a function that takes elements of \(X\) to their equivalence classes. We must also define the quotient topology as we’ve done before. This leads to the simple observation that open sets in \(A\) are just collections of equivalence classes such that the union of these classes is open in \(X\). This quotient space is called an identification space or decomposition space of \(X\).

These spaces are exciting because we can visually see their consequences. Let us look at an example. Take the real line \(\mathbb{R}\) and an equivalence relation defined by \(x \sim y\) if \(x - y\) is an integer. The partition induced by this relation is written as

\[ \mathbb{R}/\mathbb{Z} = \lbrace x + \mathbb{Z} \vert x \in [0, 1) \rbrace \]

In simpler terms, we now consider two points to be distinct only if they don’t differ by an integer. The points \(x = 2\) and \(x = 100\) are equivalent and we choose the point \(x = 0\) to represent this equivalence class. Now we get to the most interesting part. If these points are equivalent, we can bend and stretch the real line in a way that will make them coincide. In this case, we can roll the entire real line into a circle with a circumference of \(1\) unit. Because this rolling was a continuous operation (no tearing or splitting was involved), we can say that \(\mathbb{R}/\mathbb{Z}\) is homeomorphic to a circle.

![Imagine rolling the interval [0, 1] into a circle. Now imagine coiling the entire real line on this circle such that all integer points coincide.](/images/posts/quotient-spaces/real-roll.png)

Imagine rolling the interval [0, 1] into a circle. Now imagine coiling the entire real line on this circle such that all integer points coincide.

This deformation of one space into another by assuming some points to be equivalent is how we can visualize the construction of quotient spaces.

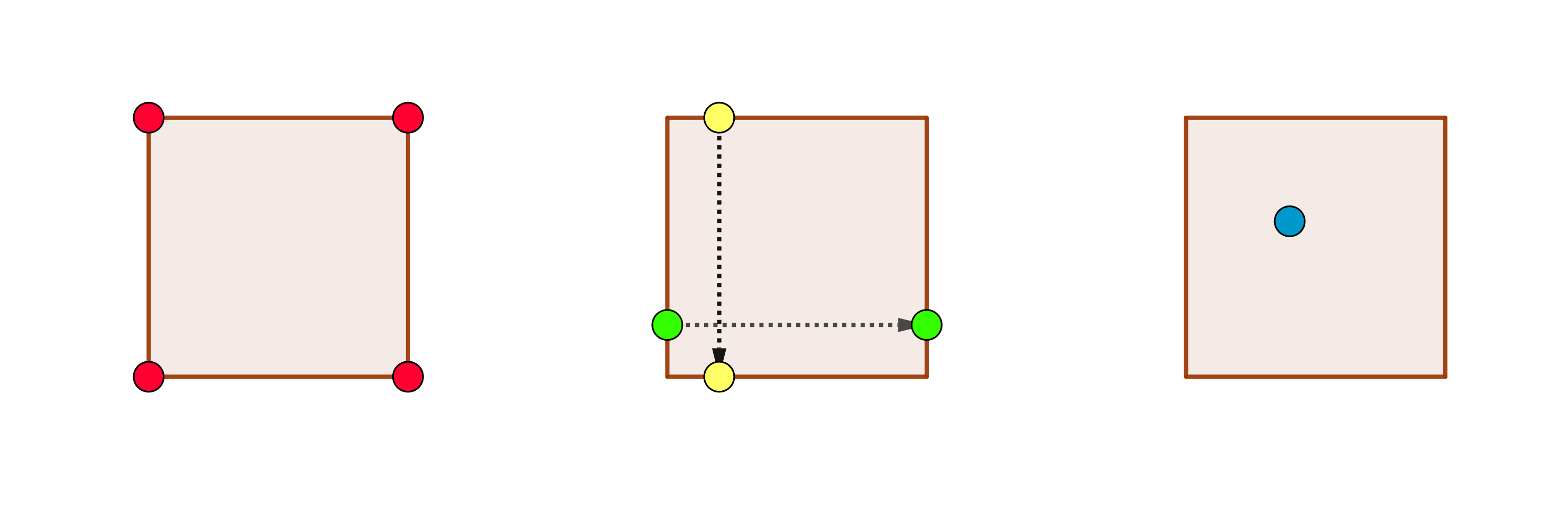

Another classic example is the construction of a torus. Think about how you will create a torus from a sheet of paper. One way to do it would be to join opposite edges into a tube and then roll the tube again to join its ends. In other words, we’re identifying opposite edges as being the same.

Rolling a sheet of paper to create a torus.

Now think about the joining process for a minute. We can only join points that are in the same equivalence class. So points directly opposite to each other on opposite edges have to be in the same class. All four corners are combined to a single point, so they should be in a separate class of their own. Finally, points on the interior of this sheet are not joined to anything at all, so they should all represent unique singleton classes. Partitioning a sheet of paper in this way and taking its quotient gives us a torus.

The four kinds of equivalence classes that make up the partition.

In a future article, we will look at this same construction from the reverse point of view. We will partition a torus to create more interesting spaces. To do this, we’ll need a more formal method of creating partitions, which is by using orbits of group actions.